Land of rocks & echoes

/The Slievetooey coastline of County Donegal in the north-west of Ireland boasts exhilarating cliffs, inaccessible beaches and an unrivalled chain of sea stacks. Lenny Antonelli spent two nights walking and wild camping in this coastal backcountry at the edge of Europe

The Great Outdoors, Spring 2016

Note: scroll down for a full set of photos

IT WOULD BE EASY to mistake Gleann Cholm Cille for the end of the earth. Here at the far-flung tip of Donegal’s Sliabh Liag peninsula, the road crosses a high empty bog on its way to the Atlantic, and you expect that at any moment, it might suddenly end on some desolate cliff-top. But then this Gaelic-speaking village appears under you like a Greenlandic outpost, a scatter of low cottages enclosed by high cliffs and mountains. Gleann Cholm Cille sits at the seaward end of an unlikely fertile valley, facing down the mercurial Atlantic.

It took me six hours and three buses to get here from Galway on a dull Friday in July. I came for a weekend backpacking trip on the wild roadless coast north of the village. My plan was to hike along the cliffs for a few hours, set up camp, then start in earnest the next morning.

As I got of the bus the sky was darkening, the wind was picking up, and rain was on the way. My mood was dark too. I don’t really know why, but it almost invariably is just before any solo backpacking trip. Once the excitement of planning and packing is over, my enthusiasm disappears and, almost always, I become overcome with a deep apathy.

Backpacking with friends is jovial and social, but heading out alone forces you confront the extremes of your thoughts and feelings. On any solo trip to the wild, my mood will swing from total elation to deep melancholy. But it usually starts of at its worst, particularly if the weather is grey, which it was that Friday evening. I knew this would change dramatically so long as I kept putting one foot in front of the other.

“Do you know where you’re going?” a man asked, as I sorted out my gear in the village. “Yes,” I said, adding nothing more for fear that if I told him, he might think I was mad. The 20km or so of coast between here and Maghera, to the north-east, includes some of Ireland’s most isolated terrain. This is a land of tremendous sea stacks, clffs and storm beaches. Not many hillwalkers come here, because most are drawn to the more accessible Sliabh Liag cliffs (595m) on the south side of this peninsula.

I walked through the village in the pale evening light, then out through meadows and pasture.The sky was marbled with dull blues and purples. I followed a bog track up to an old lookout tower on the cliffs at Glen Head. Rabbits and choughs congregated on the hillside, while the Atlantic below me had the colour and texture of mercury.

I followed the cliffs to the Sturrall, a razor-thin ridge projecting out from the coast. Local schoolteacher T.C McGinley’s 1867 book, ‘The Cliff Scenery of South Western Donegal’, tells the story of a rector’s son who wanted to collect an eagle’s eggs from this precipice. Locals tried to dissuade him, but he obsessed over the idea, and raved about it in his sleep. One morning, the boy told his mother he dreamt of walking out to the Sturrall through wind and rain to collect the eggs. After hearing about his dream, the boy’s mother left the room, and retrieved two eggs he had brought back during the night from the eagle’s eyrie, while sleepwalking.

A LONELY PLACE

Past the Sturrall, the coast descends to the old harbour and deserted village at An Port. This might be the loneliest place Ireland’s road network reaches. In 1870 the Sydney, a merchant ship, sunk nearby. Nineteen of its crew drowned; only two survived. Four of the dead are buried here.

It was almost dark when I arrived at An Port. I started putting up my tent, but the wind sent it flapping like a kite, and I struggled to put new guy lines on in the dark. When I finally had the tent up, a gust of wind knocked over my stove, spilling my pasta. My mood blackened. I carefully made dinner again and got into my sleeping bag. But heavy rain arrived and battered the tent, and it was afer 3am before I fell asleep.

I woke on Saturday morning to a grey sky and a hard wind. I ate breakfast, packed up and started climbing Port Hill. I was now about to enter real backcountry, and to follow one of the most terrific coastlines I have ever encountered.

Soon I could see Tor Mór, Ireland’s highest sea stack at 139m. Scottish climber Iain Miller was part of a team that made the first official ascent in 2008. There are dozens of quartzite sea stacks on this coast, and Miller has now made 40 first ascents.

“This coastline has the greatest collection of sea stacks in the smallest geographical area on earth,” he told me. He says one of these stacks, Cnoc Na Mara, equals Orkney’s iconic Old Man of Hoy for the quality of climbing (and Miller would know, being from Orkney). But this Donegal coast is still unknown, perhaps because it is so remote.

Just getting to the base of the stacks can mean scrambling down steep slopes and launching an inflatable sea kayak. One local story says a young man named William O’Boyle went to Tor Mór with friends to collect samphire and eggs, but became ill, and could not climb back down the stack. The tide was coming in, so William’s companions returned home, vowing to come back with help at the next low tide. But a storm blew in, and they could not get back to the stack for another week. When they returned they found William dead, and later they buried him in a coffin on the stack.

Or so the story goes — Iain Miller says he found no possible burial site on Tor Mór, or any sign at all of previous human activity. Beyond here, the coast descends to Glenlough Bay, a storm beach surrounded by ragged cliffs and steep scree slopes, from where the Glenlough River runs inland through a green and desolate valley. I followed the river’s course, watching trout hide at my approach. Now the sun was out, and the day grew hot and sticky. After eating lunch I found a still pool in the river, stripped off, and waded in.

DYLAN THOMAS AND GERMAN U-BOATS

I followed the river inland to a ruined farmstead — two cottages and outbuildings that once made a fine mountain smallholding. There are old peat beds where turf was cut, small fields where food was grown, and the Glenlough river running right past the front door. Iain Miller told me that a German U-boat commander came to own one of these cottages, though he has no idea how. But many sailors were rescued from sunken vessels along this coast, so perhaps that forms part of the story.

The Welsh poet Dylan Thomas spent the summer of 1935 at Glenlough while trying to beat his alcoholism. He was 20 years old, and had just published his first volume of poetry to critical acclaim. He rented an old cow shed that had previously been converted by the American painter Rockwell Kent.

In a letter to a friend, Thomas wrote: “Here are gannets and seals and puffins, flying and puffing and playing a quarter of a mile outside my window where there are great rocks petrified like the old fates and destinies of Ireland and smooth, white pebbles under and around them like the souls of the dead Irish. There’s a hill with a huge echo; you shout, and the dead Irish answer from behind the hill.”

Thomas spent his days writing, walking the cliffs, and fishing in the mountain lakes. His plan to dry out failed — his only neighbour was a prolific distiller of poitín, the illegal Irish whiskey. But drinking this gave Thomas strange hallucinations. On August 14, he wrote that he “looked through the window and saw Count Antigarlic, a strange Hungarian gentleman...coming down the hill in a cloak lined with spiders”. He left at the end of summer, complaining that he was “lonely as Christ”.

I climbed the hill behind the ruined cottages through thick bracken. Here on the northern side of Slievetooey mountain, the land drops into the Atlantic as 300m

cliffs. But at this tremendous height there is no real view to speak of — looking out from the edge reveals only emptiness, the land falling and disappearing into nothing, the vertical chasm difficult to comprehend.

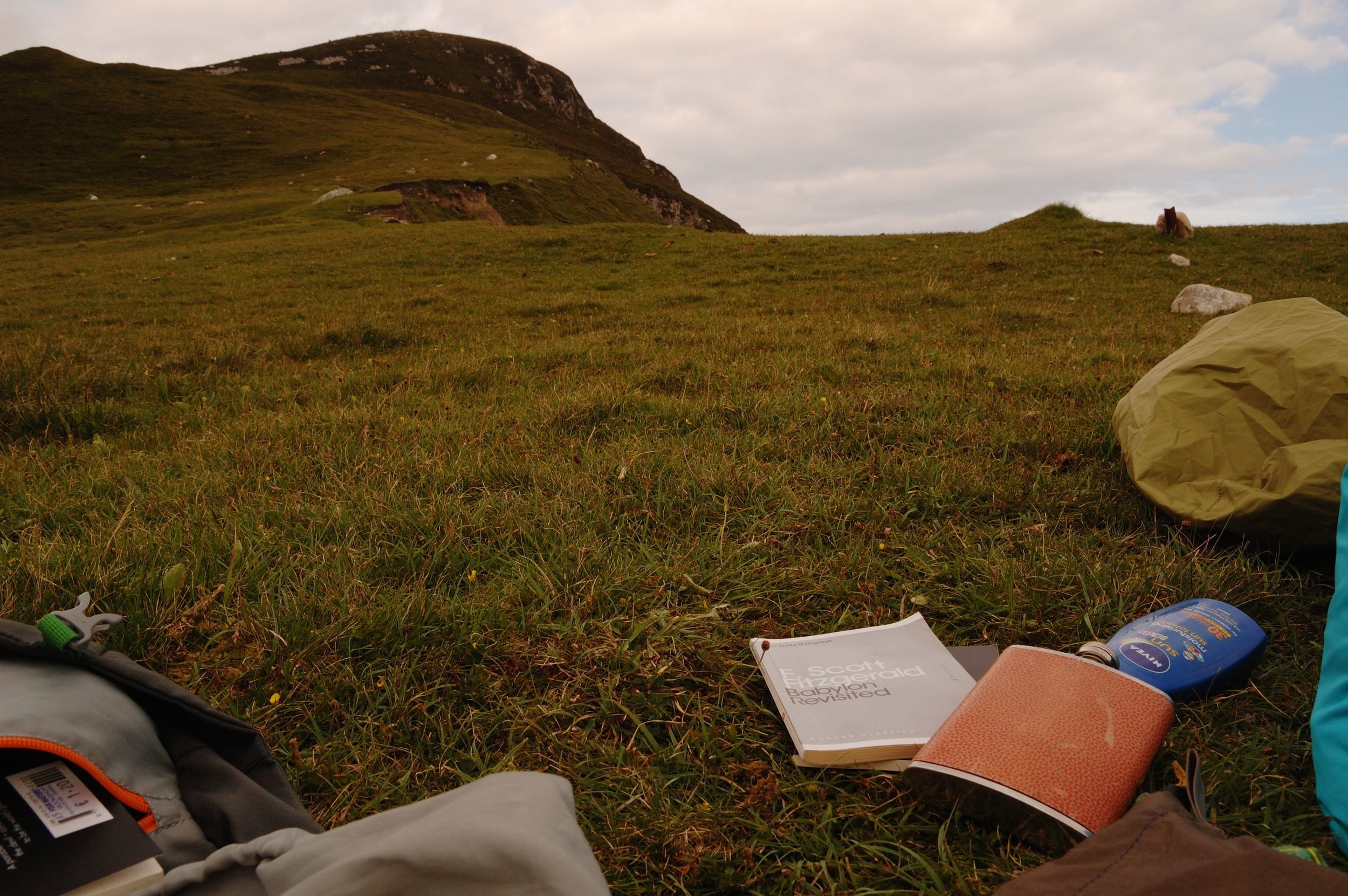

I thought about heading inland to camp at Slievetooey’s summit, but the coast was exhilarating, so I kept with it. The wind had died and, as it declined, the evening sun cast everything in bronze. I set up camp on the grassy slope across from another sea stack, Gull Island.

It may just have been the cheap whiskey I was sipping, but I don’t think I have ever experienced a sunset as rich and clear. I watched the glowing sun slip slowly behind Gull Island, then beneath the edge of the earth, turning the sky a rapturous orange. Seeing this filled me with the kind euphoria you can only get when you go to the wild alone. It reminded me why I take trips like this, and why I had walked my way though my grey mood of the previous night.

I slept long and well, and woke on Sunday morning to a blue-bright sky. The plan for the day was simple: follow the coast to the beach at Maghera, and from there hitch a lift to Ardara, the nearest town. I watched a small trawler move from cove to cove below the cliffs, its skipper checking on lobster pots.

As the coast curved, Maghera Strand came into view. Low white waves broke in chains against the sprawling shore. Civilisation was nearing, and I expected easy walking. But I didn’t pay enough attention to the map, and the terrain became tricky. The wedge of land between the mountains and the cliffs narrowed, and I found myself following precarious sheep trails on steep exposed ground (for a safer alternative to this section, see ‘How to do it’).

I scrambled down though bracken and heather to the rocky shore below. The sea was green and clear, kelps swayed with the tide, and the rockpools were speckled with red anemones. But the shore ended suddenly at the entrance to a cave. So I changed tack and climbed back upwards, higher than before. Eventually the slope eased, and I walked eastward above the cliffs.

I followed the sand dunes down to the strand. The settlement of Maghera comprises just a few bungalows on wildflower-rich pasture under Slievetooey Mountain. The tide was going out. The beach was empty. But the day was bright, and despite a forecast for thunderstorms, there was no sign of rain. I started the walking along the road to Ardara in thickening heat, feeling as high and wild as the coast I was leaving behind.

How they stack up: sea stacks of the British Isles and beyond

Tor Mor is Ireland’s highest sea stack at 139m. Britain’s most iconic sea stack is probably Orkney’s Old Man of Hoy (143m), but its highest is Stac An Armin off remote St Kilda at 196m.

In August 1727, a group of three men and eight boys who had gone to Stac an Armin hunting birds became stranded when no boat returned for them. Days became weeks, and weeks turned to months. The group survived by eating fish and birds, and sheltering in a bothy. They managed to survive the winter, and finally in May the following year they were rescued. On returning to St Kilda, they learned that a smallpox outbreak had decimated the island’s population, and that their isolation had likely saved their lives.

The world’s highest sea stack is commonly held to be Ball’s Pyramid, in the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand. The remnant of a volcano, it is 562m high and was first climbed by an Australian team in 1965. It is home to a giant species of stick insect that does not occur anywhere else in the world.

How to do it

The Slievetooey coast is on the north side of the Sliabh Liag (Slieve League) Peninsula in south-west Co Donegal. Gleann Cholm Cille (Glencolmcille / Glenculumbkille) is served by Bus Eireann (www.buseireann.ie). I started my hike by taking the Glen/Tower Loop trail (http://www.gleanncholmcille.ie/walks.htm) from the village to the tower at Glen Head, then following the coast.

Travel: There are flights to Donegal Airport (80km away) from Glasgow, and to Knock International Airport (170km away) from various UK airports.

Map: Ordnance Survey Ireland Discovery Series Sheet 10 covers this part of Donegal, and is essential. For detailed user-written hiking guides, see www.mountainiews.ie.

Logistics: For a linear walk, you’ll need to arrange transport to or from the remote settlement of Maghera (see www.ardara.ie for local taxis). There are sporadic local bus connections (www.buseireann.ie, www. mcgeehancoaches.com).

Accommodation: There are B&Bs in most towns and villages, and a hostel in Gleann Cholm Cille.

Navigation: Following this coast demands great care and good map-reading skills. As well paying close attention to the map, there are unmapped features like sudden indentations of the coast, eroding cliff edges and dangerous overhangs to watch out for. To avoid the steep ground I encountered (around grid ref G650 911) on my approach to Maghera, follow the coast from Gull Island and, as you descend after the 170m ring contour on the OS map, turn and follow the stream (G638 916) upwards and inland to Lough Acruppan. You can then descend from this lake eastward to Maghera. There is also some steep ground on the coast between the Glenlough Valley and Gull Island — generally you can avoid it by walking further inland.

Activities: Want to climb a sea stack on the way? Iain Miller (www. uniqueascent.ie) provides guided sea stack climbing.